Tackle year end like a boss

Every January we promise ourselves we’ll do things better this year. If you run a business, you might resolve to stay on top of your records all year so you don’t have to panic at tax time. But what if, despite your best intentions, tax season is looming and your records are a total mess? Here are four key steps to follow, along with some insight on using this exercise as an opportunity to better understand your business.

Step 1: Catch up on your bookkeeping

The first thing you need to do to get ready for tax time is get your bookkeeping in order. You’ll need to gather up all your receipts and bills from purchases you’ve made during the tax year, as well as your customer invoices and bank account statements.

Update your expense records

First, make sure all of your spending is recorded in your accounting system. Pay off any outstanding bills right away, and make note of any expenses that you’ve used, but haven’t been charged for yet, like phone, gas, and electricity bills. Also make note of any expenses you’ve already paid for but haven’t yet used, like insurance, rent, and some kinds of equipment. We’ll cover these a bit later.

Don’t forget to include any expenses that you pay for and also use for your business. For example, if you work from home, your rent, insurance, utilities, and repairs would count if you qualify for a home office deduction, as would certain car expenses if you use it for your business. Split the total cost between business and personal use. For home office expenses, this is usually calculated based on the work square footage vs total square footage of your home. For your car, keep logs of the business mileage you drive.

Quick tip: for home office and vehicle expenses, you may choose to allow your tax preparer or tax software to calculate the deductible amount using a standard allowance. If you’re a Wave user, you can import your Wave data to H&R Block and work with an H&R Block tax pro to catch every single deductible you qualify for. In this case, you can streamline record keeping by tracking certain items rather than actual expenses.

Update your income records

Like with expenses, make sure all your sales deposits and receipts are entered into your accounting system. Check for billable sales or services that you haven’t invoiced for yet and send those invoices out. Follow up on any outstanding invoices and send final payment reminders to late customers—start calling if you need to.

Make note of any customer deposits you’ve received for work you haven’t done yet, as well as work that you’ve started but can’t invoice for just yet. We’ll cover these in a bit.

Run your final payroll

Remind your employees to submit any outstanding expense reimbursements, and complete your payroll. Make sure this final payroll is reflected in your books, and create any necessary journal entries for adjustments after you receive your final payroll reports. Keep in mind that the final check date needs to be in 2022 in order for it to be recorded in 2022.

Reconcile your bank and credit card accounts

Make sure you’ve properly categorized and verified all your income and expenses, and that any sales taxes are accounted for within each transaction. (If you’re using an accounting software, doing this will automatically update your financial reports.) Then reconcile your bank and credit cards to make sure all of the transactions in your monthly statements appear in your accounting records, and that there aren’t any duplicates.

Don’t make these common mistakes:

- Determine how to account for asset purchases on your books and taxes. Your capital assets and equipment purchases will be treated differently than other types of expenses such as wages and professional fees.

- Make sure you’re consistent with how you record your inventory purchases. Goods and materials for resale are considered inventory, and there are two ways to record them. The easiest way is to record inventory purchases as a cost of goods sold (COGS) expense, with periodic adjustments to reflect physical inventory. Or, you can record each inventory purchase as an asset, and post regular journal entries to capture the inventory sold as a COGS expense. Either way, you’ll need to count and calculate the value of your inventory regularly (see below).

- Personal withdrawals for a business owner aren't business expenses. Keep track of them and provide the information to your tax preparer.

- Don’t record loan payments as an expense. They should be split between principal payment on the loan and interest expense (see below).

Step 2: Make year-end period adjustments

Now that you’ve updated your income and expenses, it’s time to tackle year-end period adjustments. These adjustments are journal entries made to your business accounts at the end of a period so your financial statements accurately reflect your business performance.

In accounting, we break up the life of a business into segments so that we can more easily follow its progress. A period can be any duration, but most companies use a fiscal year. This is so you can close out the books at the end of that fiscal year, and properly preserve the connection between expenses and the revenue they generate.

Adjustments for every business:

The next four adjustments should be considered by every business at the end of the year, regardless of size, legal structure, or ownership. Your accountant will ask you about these items, so if you can get it done before you hand over your books, it’ll save them time (and save you money).

1. Inventory adjustments

As mentioned above, if you buy inventory for your business and then resell it, that’s a Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) expense. If you buy inventory and don’t sell it, that’s actually an asset. So throughout the year, as you buy inventory, you’ll record it as either a COGS expense, or as an asset.

At the end of the year, you’ll want to know how much of that inventory actually represents expenses, and how much actually represents assets. Once you determine how much inventory you have at the end of the year, you’ll need to make an adjustment so that the value of that inventory is accurately reflected in your books. If you take these inventory counts regularly, you can keep a close eye on which products are best-sellers, and which products are tying up your cash by sitting on the shelf.

If you record all inventory purchases into an asset account, the journal entry to record COGS will be a debit to COGS expense and a credit to the inventory asset account. If you record all inventory purchases into the COGS expense account, the journal entry to record COGS will be a debit to the inventory asset account and a credit to the COGS expense account.

In both cases, the amount of the entry will be the difference between the balance in the inventory asset account (before you make the entry) and the actual value of the physical inventory you have on hand. You should run the balance sheet report after making the entry to make sure the ending inventory balance equals what you calculated.

2. Bad debt adjustments

Sometimes you don’t get paid for your work. If you’ve followed up with a client but it looks like you’re never going to get that payment, you can write off those invoices and move the receivable to bad debt expense. Depending on how your accounting system tracks invoices, you might need to follow a specific set of instructions so that your aged receivables report doesn’t include these bad debts. If you want to simply make a journal entry, you will debit bad debt expense and credit accounts receivable.

3. Reconciling loan accounts

If you’ve taken out a loan and you’re making payments throughout the year, part of those payments will be principal repayment, and the rest will be interest paid to the lender. At year end, you’ll want to look at your final loan statement, and make sure the loan balance in your books matches the loan balance on the statement. If it doesn’t, you’ll need to make an adjustment so that your books reflect the actual amount you paid in principal and interest.

The journal entry will be made to the loan payable account and the interest expense account. Depending on how you’ve entered the loan payments, you might need to increase (credit) or decrease (debit) the loan payable balance; either way, the other half of the entry will be to interest expense. You should run the balance sheet report after making the entry to make sure the ending loan payable balance matches the loan statement. It’s easy to make an entry going the wrong way!

Depreciation adjustments

The assets you purchase are recorded at cost, but they depreciate over time. Some assets have physical depreciation, due to wear and tear, or exposure to the elements (e.g., a vehicle). Others have functional or economic depreciation, where the asset becomes obsolete or just less useful over time (e.g., software).

You’ll need to record your assets’ depreciation regularly. This journal entry is a debit to depreciation expense and a credit to accumulated depreciation (which is on the balance sheet). Some companies record it quarterly, some annually, and some even do it monthly.

You can use a few different methods to calculate it, including fixed percentage, straight line, and reducing balance methods. Your accountant can help recommend the best approach for your business and provide the depreciation schedules for your assets. You may choose to record the amount of depreciation reported on your tax return each year; in this case, you can wait until after your income tax return is filed.

Adjustments for accrual-basis companies:

These adjustments only need to be done by companies which report on an accrual basis, either for financial reporting (like if you provide financial statements to a lender or an investor), or for tax reporting (your tax preparer can tell you if you’re not sure).

Quick tip: if you run a sole proprietor business, you can most likely skip these.

Customer deposits

Remember back in step one, when we suggested you make note of payments you’ve received where the work hasn’t been done yet? Now you’ll want to record those deposits by creating a journal entry: credit a liability account for deposits, and debit the revenue account where the payment was originally recorded. The reason you’re recording it as a liability is because you still have an obligation to fulfill the work, and it’s technically not income until the work is done.

When you eventually ship the customer order or complete the contracted work, you’ll enter a reverse journal entry, debiting the deposit liability account and crediting the revenue account.

Prepaid expenses

Let’s go back to the unused, prepaid expenses that you made note of in step one. Create a journal entry to record those payments as a debit to an asset account for prepaid expenses, and a credit to the original expense account. When you eventually use that prepaid expense, you’ll enter a reverse journal transaction debiting the expense account, and crediting the prepaid expense account.

Recognizing accrued revenue

Accrued revenue is work you’ve done, but that you haven’t had a chance to invoice for yet. You’ll record a revenue accrual journal entry as a debit to an asset account for accrued sales, and a credit to revenue. Once you invoice for the work, don’t forget to record an entry to reverse the accrual.

Recognizing accrued expenses

Accrued liabilities reflect expenses on your income statement that won’t get billed until the next fiscal year, but that need to be recognized in this fiscal year because that’s when you incurred them. You’ll record an expense accrual journal entry as a credit to a liability account for accrued expenses, and a debit to the expense account. Once you receive the bill, don’t forget to record an entry to reverse the accrual.

Step 3: Convert accrual to cash

There are two standard ways that you can do your accounting: accrual-based and cash-based. Accrual-based accounting means you recognize income and expenses when they are earned or incurred, as opposed to cash-based accounting, where you recognize them once they’re received or paid.

Under the accrual method, when you make a new sale you record the sale as income even if the client isn’t going to pay for a few weeks. Under cash-based accounting, you wait until the client pays you before you record that sale. Similarly, you record your January phone bill as an expense in January under accrual accounting, but with cash accounting you record it in February once it’s paid.

Accrual accounting is what we recommend at Wave because it gives you a more accurate picture of your business performance. That being said, when it comes time to file a tax return, most smaller businesses report income and expenses on a cash basis.

Converting to cash from accrual

Your accounting software may offer cash-basis reports, or your accountant can do the conversion for you. If you’re a Wave user, check out this article in our Help Center for instructions on using our cash-basis reports.

Step 4: Send your records to your accountant

Once you’ve caught up on your bookkeeping, made the necessary adjustments, and converted your income and expenses from accrual to cash basis (if necessary), you’re ready for year end. The final step is to pass your books along to your accountant to work his or her magic.

Year end is a crazy time for accountants too, so you’ll want to make the transition as smooth as possible. Think of your accountant as someone who’s there to check your work and make recommendations, not to do bookkeeping for you; it’ll reduce the number of questions you have to answer, and hopefully result in a lower bill as well. Make sure you share the following reports with your accountant:

- Trial balance

- Balance sheet

- Profit & loss statement

- Period matching adjustment journal entries

Your accountant may also ask for a copy of the general ledger report, which shows all transactions for the year. This helps them track down any mysterious balances or activity in your accounts.

Now that your books are ready for tax time, you’re in a great position to review your business performance, and make strategic decisions to help your business grow. Just make sure to file your taxes as soon as possible to avoid any penalties.

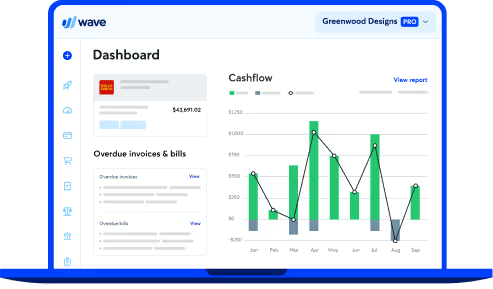

Let Wave and H&R Block file your taxes for you

If you’re based in the US, we suggest using Block Advisors, part of H&R Block to get your taxes prepared affordably with 100% accuracy guaranteed (which is super quick to set up, BTW!). You can import your Wave accounting data straight into H&R Block and get paired with a personal tax pro who will take care of your tax filing for you or just help you out when you need it.

You’ll feel more confident, cut down hours of work, receive personal 1:1 advice, get all the latest info on tax deductions, and much more. Simply log into Wave and click the “Tax Filing” link in the navigation menu to get started.

(and create unique links with checkouts)

*While subscribed to Wave’s Pro Plan, get 2.9% + $0 (Visa, Mastercard, Discover) and 3.4% + $0 (Amex) per transaction for the first 10 transactions of each month of your subscription, then 2.9% + $0.60 (Visa, Mastercard, Discover) and 3.4% + $0.60 (Amex) per transaction. Discover processing is only available to US customers. See full terms and conditions for the US and Canada. See Wave’s Terms of Service for more information.

The information and tips shared on this blog are meant to be used as learning and personal development tools as you launch, run and grow your business. While a good place to start, these articles should not take the place of personalized advice from professionals. As our lawyers would say: “All content on Wave’s blog is intended for informational purposes only. It should not be considered legal or financial advice.” Additionally, Wave is the legal copyright holder of all materials on the blog, and others cannot re-use or publish it without our written consent.